Cooperative Tax Compliance Programs: A Great opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean

Tax collection in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) remains a major challenge for the governments. The tax evasion rates remain significant despite great efforts by tax administrations (TAs) to strengthen their capacities.

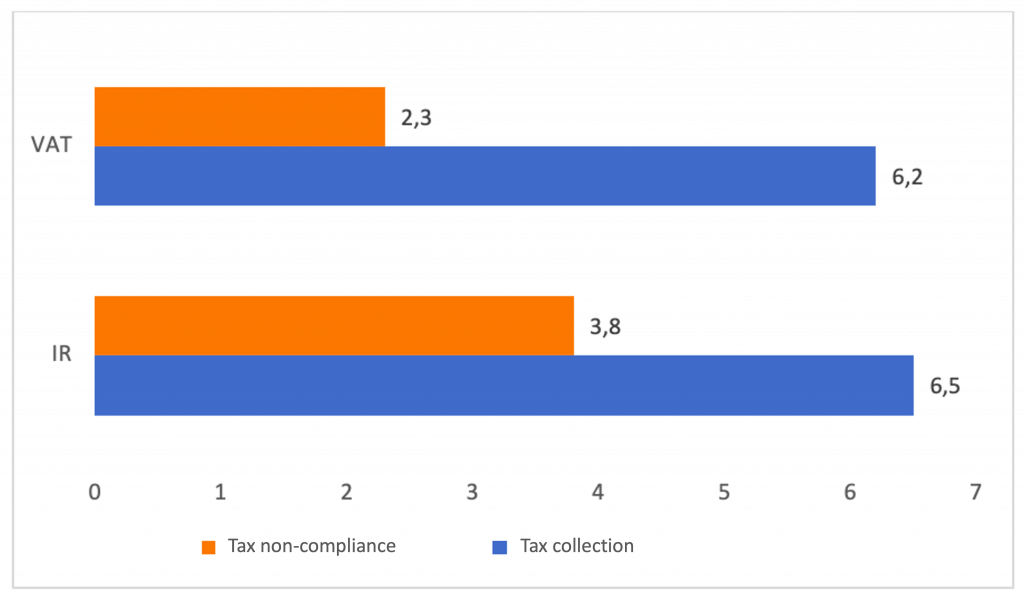

The 2020 data from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) show that uncollected revenue for 2018 amounted to 6.1% of the regional GDP. The percentage of evasion of personal and business income tax remains high at 3.8%[1] as well as the percentage of evasion of Value Added Tax (see Figure 1). To address this challenge, many countries are adopting cooperative tax compliance programs, the progress, benefits and challenges of which we will discuss in this blog.

Figure 1. Latin America: non-compliance with income tax and value added tax (VAT), 2018 (percentage of GDP)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

But before we discuss the advantages of the cooperative model, we need to understand the limitations of the traditional control model, known as the vertical model. In this model it is considered that the taxpayer is aware of what the tax legislation requires, so that he can calculate his tax obligations for the corresponding payment. Once the payment is received, the TA then evaluates it by issuing a criterion on the fulfilment of these obligations.

However, these basic models raise friction and questions between active and passive subjects, which in many cases result in tax litigation that not only delay collection, but also generate additional expenses for both the tax administration and the taxpayer. Understanding why tax laws are being complied with or not, and the reasons behind the behavior are important issues for tax administrations and are basic to the design of a risk model. However, the models that explain the taxpayer behaviour also present limitations, such as the tax planning of large companies, which in some cases are aggressive.

These facts lend themselves to reflection, considering it necessary to rethink the techniques and approaches used, especially for a taxpayer with a good record of tax compliance and good corporate governance.

Cooperative tax compliance models

Since the mid-2000s, some countries began to design and implement cooperative tax compliance models, which aim to reduce the level of uncertainty for both taxpayers and the TA. The model is based on a horizontal relationship based on cooperation that guarantees timely and accurate tax compliance, which in turn avoids contingencies and litigation [2]. This model differs from the approach of a basic relationship based on an obligation, which is the vertical model.

According to the Inter-American Center of Tax Administrations (CIAT), the cooperative tax compliance model seeks to ” achieve significant improvements in the level of mutual transparency and consequently in the level of voluntary compliance, with the objective of reducing compliance and/or administration costs, and as far as possible prevent disputes in the legal– tax relationship.”

That is, the concept of cooperative compliance was developed as a way to reconcile improvements in tax compliance with a good business environment as an element of an overall compliance strategy. It is security in exchange for transparency[3].

Lessons learned from the countries’ experiences

The impact of cooperative compliance models and programs has been diverse by country. For some it was considered a radical change, and for others it was a modification of those already implemented. Countries such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands were pioneers in implementing these models.

In some countries, the cooperative compliance model has focused on the main taxpayers, especially the large ones, who have a significant share of the collection,[4] and in others it has also included medium and small taxpayers, but in both cases it is considered an alternative method to ensure a level of tax compliance.

Today, around 30 countries have cooperative compliance models, highlighting some European countries for their progress and achievements, such as: Denmark, Finland, Holland, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom[5]. Latin America and the Caribbean are taking their first steps in this regard, highlighting Brazil, one of the first countries to develop a federal cooperative compliance program called CONFIA[6]. This program accompanies cooperative compliance initiatives[7] from several Brazilian states.

Despite the absence of universal cooperative compliance models, an analysis of the experience of different countries demonstrates three characteristics in common: the ability to assess risks, to work in real time, and mutual understanding[8].

On risk assessment, the model facilitates the determination of which taxpayers require more or less follow-up. Working in real time eliminates the need to wait for the tax return that needs to be audited and that can lead to tax litigation. For the mutual understanding, TAs must place highly qualified officials in these compliance programs, considering the business types and business reality of specific taxpayers. Only in this way will they be able to understand the needs and challenges of such taxpayers, thus fostering not only understanding between the parties, but security. In parallel, taxpayers must be transparent in their activities.

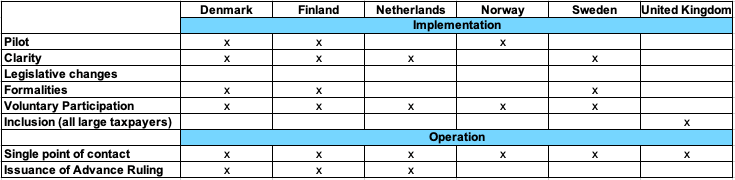

In addition, the countries’ experience also indicates that the implementation of successful cooperative tax compliance models requires: a pilot (plan), clarity, legislative change, formality, voluntary participation, and inclusiveness (all large companies). For their operation, these models require a single point of contact and provision of advance resolutions. Figure 2 shows these specific characteristics as it is the case for some European countries.

Figure 2. Key features of the cooperative compliance model

Source: Larsen, B. & Oast, L. (2019) “Taxation Large Businesses: Cooperative Compliance in Action”, Intereconomics, No. 3, Volume 54.

Source: Larsen, B. & Oast, L. (2019) “Taxation Large Businesses: Cooperative Compliance in Action”, Intereconomics, No. 3, Volume 54.

Leveraging technology

At the same time, technology has made a great deal of information about taxpayers available to tas. The automation and standardization of technological processes internationally are progressively facilitating more accurate and timely information from taxpayers locally and abroad, although it is worth mentioning that there are important challenges to be overcome. In addition, it is essential to take into consideration that, when designing or implementing a program, the conscience and morality of citizens about the payment of taxes, as well as their discipline and perception of the environment where they have the tax obligation, are taken into account[9].

For successful implementation, it is important to conduct an evaluation of the efficiency and effectiveness results. It is therefore necessary to consider the importance of benchmark; to analyze the effective tax rate of program participants and non-participants; compare the increase or decrease in litigation and length of litigation and amount of taxes in dispute; evaluate the taxpayer’s level of risk (comparison of taxpayers who are in and out of the program); and conduct confidence and satisfaction surveys.

In this regard, the IDB, through several projects, alliances and knowledge exchange events, supports the TAs’ initiatives in the region for the development of cooperative compliance projects as a way to recover tax revenues, increase trust, reduce litigation and improve communication.

This is the case of the CONFIA Program promoted by the Federal Revenue from Brazil[10], based on the paradigm of the relationship focused on justified trust, which seeks to offer greater legal security to taxpayers committed to tax compliance and willing to be transparent with the tax administration.[11] The basis of the program is risk management, analysis of the taxpayer behavior and compliance history, in addition to the fiscal control structure of companies.

The model is currently in the design stage, with the participation of a group of large companies selected according to objective and public criteria[/12].

It is expected that the program can contribute to the reduction of tax litigation, which in 2021 reached 922 billion reais (US$177 billion), with approximately 45% of the total being concentrated in only 145 processes.[13]

The experience with this program was one of the topics discussed by TA representatives in Brazil during the XVI National Meeting of Tax Administrators (ENAT) in December 2021, a knowledge exchange event organized with our support.

[1] Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean( ECLAC), Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2020 (LC / PUB.2020/6-P), Santiago, 2020. Available in: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45731/S2000153_en.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

[2] Szudoczky, R. & Majdanska, A. (2017), Designing Co-operative Compliance Programmes: Lessons from the EU State Aid Rules for Tax Administrations British Tax Review, Vol. 2017, No. 2, 2017.

[3] Owens, J. & Leigh Pemberton, J. (2021), Cooperative Compliance: A Multi-Stakeholder and Sustainable Approach to Taxation Wolters Klywer, Eucotax.

[4] Large taxpayers are responsible for 30% to 60% of net revenue. On average ,2% of legal entities correspond to 43% of the total collection. Source: Tax Administration 2021-comparative information on OECD and other advanced and emerging economies pag. 113,

[5] Larsen, L. & Oast, L. (2019), Taxing Large Businesses: Cooperative Compliance in Action, Intereconomics, No. 3, Volume 54.

[6] https://www.gov.br/receitafederal/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/confia

[7] Sao Paulo: nos conformes; Rio Grande do Sul: nos conformes; Alagoas: contribuinte arretado; Piaui; Contribuinte legal; Rio Grande do Sul: contribuinte exemplar; among others.

[8] Owens, J. & Leigh Pemberton, J. (2021), Cooperative Compliance: A Multi-Stakeholder and Sustainable Approach to Taxation Wolters Klywer, Eucotax.

[9] Pablos, L. & Alarcon, G. (2007), La conciencia fiscal y el fraude fiscal: factores que inciden en la tolerancia frente al fraude, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Gonzalez, D. (2020), Morality, conscience, and tax discipline: their role in tax compliance, CIAT and The inspection of Large Companies: the cat and mouse strategy or the Horizontal Monitoring Model, CIAT (HTM).

[10] The IDB is currently implementing technical cooperation with Receita Federal to strengthen tax compliance.

[11] Receita Federal de Brasil, Programa CONFIA. Available in: https://www.gov.br/receitafederal/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/confia

[12] https://www.gov.br/receitafederal/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/confia/CRITRIOSSELEOGRUPOSECONMICOSCONVIDADOSFDCONFIA.pdf

[13] https://carf.economia.gov.br/dados-abertos/dados-abertos-202201-final.pdf

4,257 total views, 4 views today