Transfer pricing and VAT: analysis of recent CJEU jurisprudence and its implications for Latin America

I. Introduction

In the tax field, two logics coexist that, although related, speak different languages. On the one hand, transfer pricing, as a set of rules specific to direct taxation, requires performing transactions between companies of the same group as if they were transactions between independent parties, at market values. Its objective is to distribute profits fairly between jurisdictions and avoid the erosion of taxable bases in the Income tax of legal entities.

In parallel, the Value Added Tax or Added Value (VAT) responds to another logic. As an indirect consumption tax, it does not pursue a theoretical market value, but the amount actually paid in each transaction. In this way it ensures neutrality, since for companies VAT should not be a cost, but a tax that falls on the final consumer[1].

This contrast between “market value” and “paid value” has been the subject of repeated pronouncements by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU)[2]. A practical consequence follows from this difference: transfer pricing adjustments – such as those made at the end of the fiscal year to align margins with intra—group policy – do not automatically generate an adjustment in the VAT taxable base. If this were to happen, it would distort the principle of ‘subjective value’ enshrined in Directive 2006/112/EC. Therefore, for years the practice in Europe was to consider that, except for actual additional consideration, these adjustments fell mostly outside the scope of VAT.

However, recent developments have contributed to a more nuanced analysis. In the Weatherford judgment (C-527/23), the CJEU recalled that denying the right to deduct VAT on intra-group services based on transfer pricing policies undermines the neutrality of the tax, so that if the services are real and contribute to the taxed activity, the input VAT should be deductible.[3]. In the judgment in Högkullen (C-808/23), the debate revolved around how to determine the ‘normal market value’ in related-party transactions, concluding that in some cases the valuation for VAT purposes may differ from that fixed in transfer pricing. And in the Arcomet judgment (C-726/23), which we will comment on below, the Court went one step further by considering that certain year-end adjustments, far from being mere accounting entries, actually constitute part of the price of services provided within a group and, therefore, should be subject to VAT.

These examples show that the dividing line between the two worlds is not static. European law is moving towards an approach in which the actual economic content of intra-group adjustments is what determines their VAT treatment. The border between direct and indirect taxation thus becomes a space for constant dialogue between rules, courts, and tax administration.

II. The recent judgment of the CJEU Arcomet.

II.1 Background.

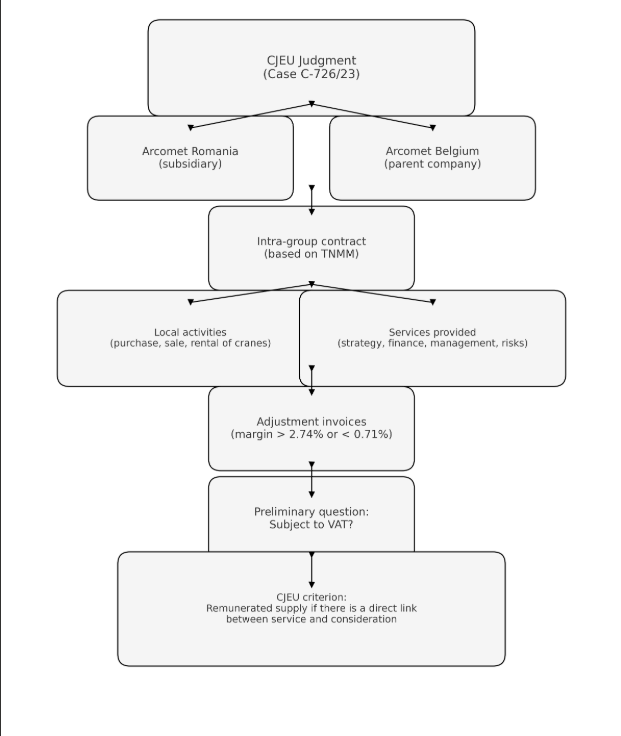

The Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) of 4 September 2025 (Case C-726/23, ECLI:EU:C:2025: 646) rules that the amount invoiced by one company to another company belonging to the same group of companies, which makes it possible to adjust the latter’s operating margin according to the Transactional net margin method (TNMM), in accordance with the OECD Guidelines[4], constitutes compensation for a service provided by the first company and, consequently, implies the existence of a service rendered for consideration, within the meaning of art. 2.1.(c) of the VAT Directive.

The facts are as follows: Arcomet Belgium (parent company) and Arcomet Romania (subsidiary) are part of an independent global group in the crane rental sector. They sign a contract, under which each party undertook to perform a series of benefits in favor of the other. On the one hand, Arcomet Belgium undertook to assume, from an operational point of view, most of the commercial responsibilities, such as strategy and planning, negotiation of contracts (framework) with third-party suppliers, negotiation of terms and conditions of financing contracts, engineering, finance, fleet management at central level and quality and safety management. In addition, it bore the main economic risks linked to the activity of Arcomet Romania. On the other hand, the latter undertook purchasing and possessing all the products necessary for the exercise of their activity and to be responsible for the sale and rental of said products, as well as for the provision of services.

The remuneration for the activities conducted by the parties is equal to the amount necessary to place Arcomet Romania in a position corresponding to the activities it performed and the risks it assumed and this position had to be determined by mutual agreement between the parties and based on the operational net margin method, established by the OECD Guidelines. According to the methods of determining such remuneration, formulated in the Annex to the same contract, Arcomet Belgium was required to issue an annual adjustment invoice if the operating margin of Arcomet Romania was higher than 2,74 % in order to recover the excess profit, or by Arcomet Romania if such margin was lower than 0,71 %, in order to cover any excess losses. On the other hand, no remuneration was due when the operating margin in question fell between 0,71 % and 2,74 %.

However, during the years 2011, 2012 and 2013, the Romanian company exceeded this margin. To adjust it, the Belgian company issued invoices to its subsidiary for the excess amount, classifying them as” services”.

That question for a preliminary ruling arises from the fact that the Romanian tax authority, following an inspection, refused the subsidiary the right to deduct VAT from those invoices. The Administration argued that the company had not been able to demonstrate either the reality of the services provided or their direct connection with the company’s taxed operations.

II.2. The legal reason for understanding that transfer pricing adjustments should be subject to VAT.

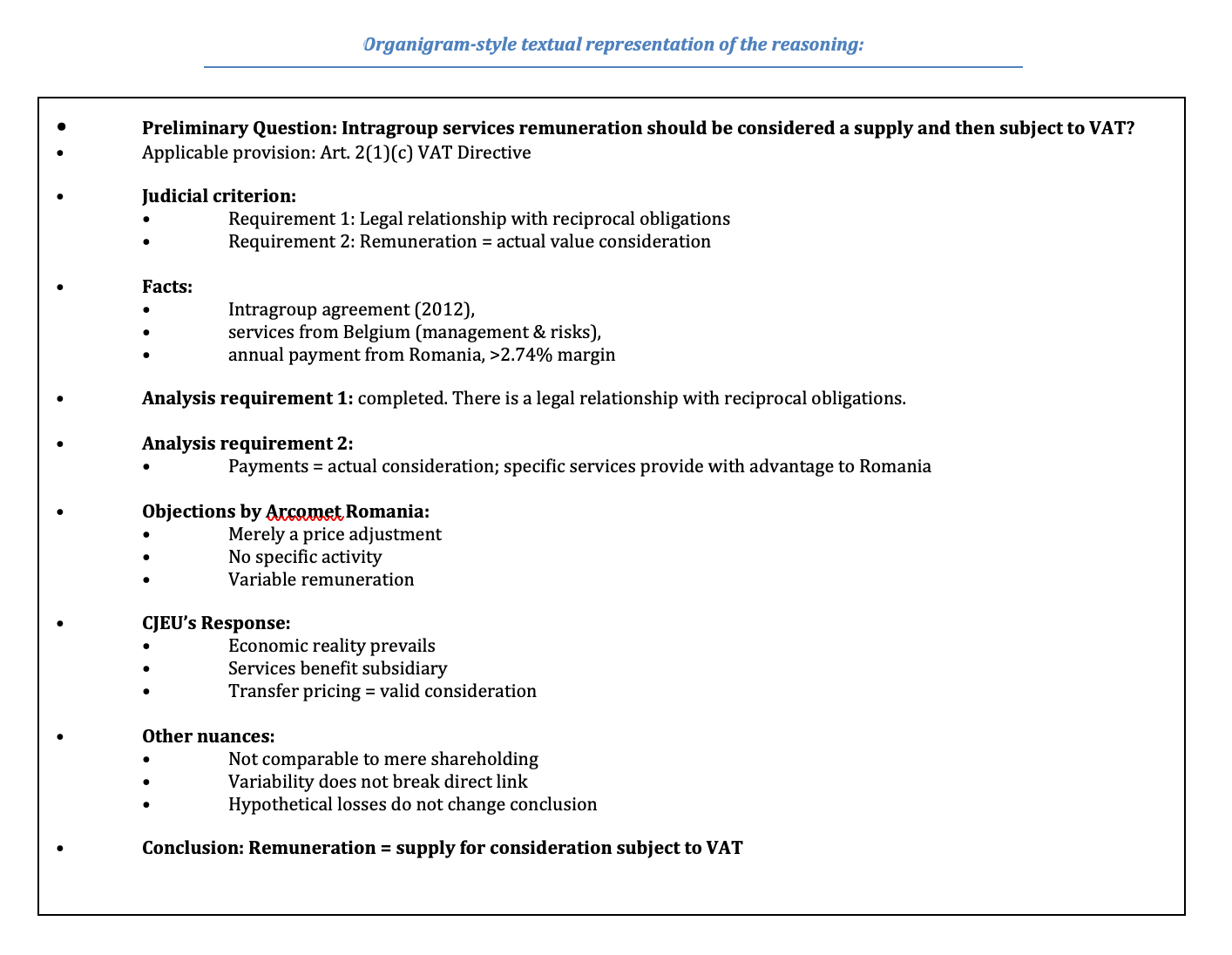

When the Arcomet case reached the Court of Justice of the European Union, the question seemed technical: could a transfer pricing adjustment, under certain conditions, be subject to VAT? However, behind that question there was a deep-rooted dilemma: what weighs more in VAT, accounting forms, or the economic reality of operations?

In response, the Court relied on a well-established principle in the VAT Directive, which is that a supply is only considered to be made “for consideration” if there is a legal framework in which the supplier and recipient exchange reciprocal services, and if the remuneration received constitutes the true countervalue of the service provided. It is not enough that there is a payment; there must be a direct and verifiable link between that payment and a specific service.

With this basic idea, the Court analyzed the facts. Arcomet Romania paid its Belgian parent company under a contract, according to which the remuneration was fixed according to objective criteria, established in advance, and with a method endorsed by the OECD. The fact that the remuneration was variable did not make it random: each year they calculated the adjustment according to previously agreed rules, so that, during 2011, 2012 and 2013, the outcome was payment in favor of the parent company. This systematic pattern convinced the CJEU that we were not dealing with an empty accounting entry, but with compensation for real services provided.

The Court also ruled out classifying these payments as free, uncertain, or lacking economic cause contributions. On the contrary, the link between service and remuneration was direct, since the parent company assumed certain management and support functions, and the subsidiary paid for it. Thus, the transfer price adjustment in this case became the actual price of an intra-group service subject to VAT.

This judgment, however, does not appear as a general doctrine applicable to all cases. The CJEU was explicit in pointing out that its reasoning depended on the facts of the case, the way the parties drafted the contract and the specific nature of the payments. Consequently, we should examine each intragroup operation in its own context, without automatic extrapolations.

And here lies an important teaching. The Court recalled that tax administrations should not accept a generic invoice without further ado. They can, and should, request additional documents: detailed contracts, explanations about the nature of the services, rules for calculating remuneration, reference periods. Only in this way can they verify if the payment responds to a real and necessary service for the activity of the subsidiary, or if it is a mere accounting adjustment mechanism disguised as a benefit.

For multinational companies, the caveat is to carefully review their intra-group contracts, especially those that apply the TNMM method. If the contractual terms do not allow identifying the underlying services, or if the remuneration appears as a closing adjustment without specific cause, the risk of the authorities rejecting the VAT deduction is real. On the other hand, robust and accurate documentation reinforces the position that this is a legitimate consideration.

In conclusion, the Arcomet judgment reflects a shift towards the substantive, as the CJEU prefers to look at economic reality rather than formalities. Thus, not every transfer pricing adjustment should be subject to VAT, but when the facts show that there are services provided and remunerated under clear rules, the tax does come into play.

III. Conclusions for Europe and Latin America.

The judgment of the CJEU Arcomet extends beyond Europe. Its echoes also resonate on the other side of the Atlantic, where tax administrations have been strengthening the control of intra-group services and transfer pricing adjustments for years.

In many Latin American countries, VAT works under a logic similar to the European one. That is, they tax the value actually paid in each transaction. However, the lack of specific guidelines on the treatment of transfer pricing adjustments has created a grey area. When a subsidiary receives a supplementary charge from its parent at the end of the year, is it a simple accounting adjustment for income tax, or a service provision subject to local VAT?

This is where the teaching of the CJEU becomes relevant. The Court has made it clear that the form is not enough — an invoice with the label “TP adjustment” – the decisive thing is the substance. If there are actual services behind the adjustment, described in a contract and quantified according to objective rules, that payment constitutes an onerous consideration and must be subject to VAT. Latin American administrations can easily adopt this reasoning, in their effort to align with the BEPS standard, seek to close gaps that allow the erosion of the tax base or double non-taxation. The criterion of the Arcomet Judgment reinforces the legitimacy of these demands. Administrations can and should go beyond the invoice to verify the economic substance of the operation.

But there is also a caveat, given that applying this nuanced logic could lead to double taxation risks. If a Latin American country taxes a transfer pricing adjustment as a service subject to VAT, while the counterparty jurisdiction does not recognize it as such, the group may end up bearing an unforeseen cost. Therefore, the message of the judgment is not to mechanically replicate the European solution, but to adapt the central principle, that is, to examine the reality of intra-group services on a case-by-case basis and to harmonize, as far as possible, the criteria between countries.

In any case, and in general, the analyzed judgments emerge as a catalyst for substantial transformation in the articulation between transfer pricing and VAT, promoting the adoption of comprehensive approaches. This approach not only seeks to consolidate regulatory coherence, but also to significantly mitigate the tax risks faced by multinationals, thus constituting a milestone in the evolution of the international tax system.

References:

[1] J.M. López-Alascio Torres, “VAT and transfer prices. New perspectives”, https://blogfiscal.cronicatributaria.ief.es/iva-y-precios-de-transferencia-nuevas-perspectivas/ (Accessed WEB September 22, 2025).

[2] CJEU case-law: Cases C-412/03 (Hotel Scandic), C-285/10 (Campsa), C-210/04 (FCE Bank), C-527/23 (Weatherford Atlas), C-808/23 (Högkullen AB), C-726/23 (Arcomet). In these cases, the Court has insisted that the VAT taxable base is the actual consideration agreed between the parties, without it being able to be replaced by a market estimate.

[3] G. Echevarría Zubeldia“ “Intragroup Services, Transfer Pricing and VAT”, https://revistas.laley.es/Content/Documento.aspx?params=H4sIAAAAAAAEAMtMSbF1jTAAAiMzYyNjS7Wy1KLizPw8WyMDI1MDQyNDtbz8lNQQF2fb0ryU1LTMvNQUkJLMtEqX_OSQyoJU27TEnOJUtdzEkpLUIlvnxKKQoswkKNc7tdI2yDXMMzjEUS01KT8_G8WqeJgVACpRGkeEAAAAWKE (Accessed WEB September 22, 2025).

[4] OECD (2022), OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0e655865-en

6,839 total views, 12 views today