Management of the floating tax debt

The management of tax debt is one of the main pillars of the tax administration. The lack of timely payment by taxpayers is an overly sensitive issue for the efficient management.

Hence, in the face of such an occurrence or possibility of becoming concrete, dissimilar strategies can be formulated to avoid its negative consequences for the public treasury.

But if payment is the main objective, the secondary or collateral effects of the measures adopted must not be neglected, as they affect the general behavior of taxpayers[1].

First of all, the validity of the saying “bread for today and hunger for tomorrow” should be avoided, since the granting of excessive advantages to defaulters to regularize their debt can motivate non-compliant tax behaviors in the rest of the taxpayers.

Tax debt

Within the concept of tax debt, one can distinguish: a) floating debt, and b) liquid and enforceable debt.

The first is made up of overdue debt but extended by a new maturity (deferral) or by its adherence to payment facility plans (fractionation, partialities, etc.).

While the liquid and enforceable debt is the one determined by the obligor or by the tax administration and in the event that it has been disputed, it is final, that is, the administrative, contentious-administrative, or judicial proceeding have been exhausted and a ruling in favor of the tax authorities has been issued. This debt is enforceable and therefore its collection by executive or coactive means (administrative or judicial) is enabled.

Floating tax debt

With respect to this category, the tax agency may adopt a) an extreme attitude of not applying any deferral or partial payment regime under the premise that a tax administration should not become a financial entity, and b) apply one or several regimes depending on the circumstances of each case.

Countries have adopted the second position, but not uniformly, so there are significant differences in the conception.

Payment Facilitation Plans

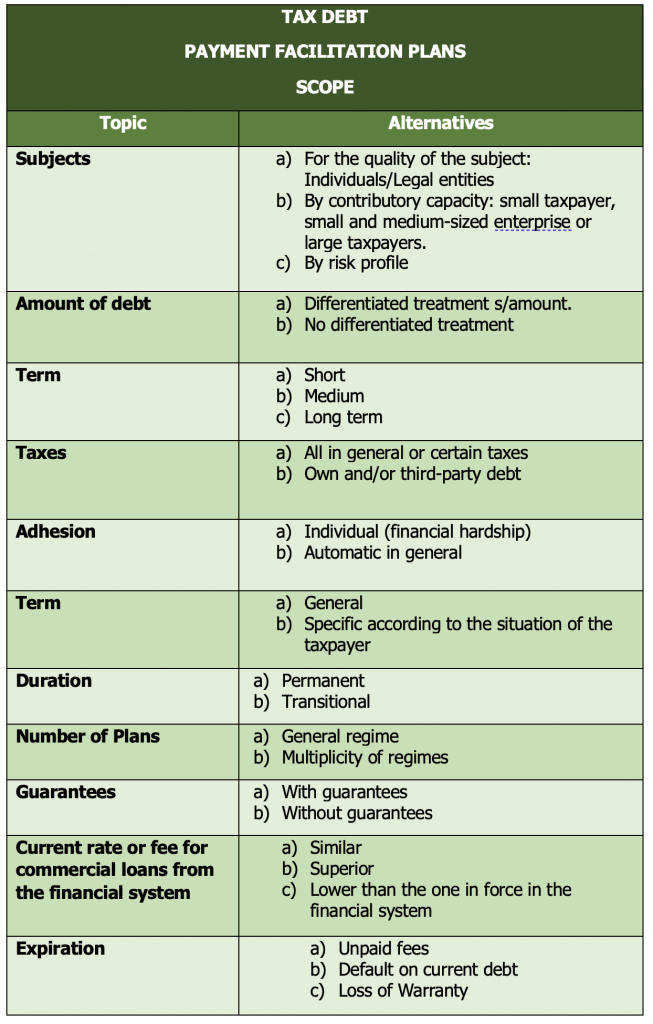

To propose a suitable strategy, it is necessary to describe the essential elements that must be included in the formulation of a payment facilitation plan:

Analyzing the current plans of certain countries in the Americas (Argentina, Brazil, USA, Mexico and Peru) and from Europe (Belgium, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and the United Kingdom) the following conclusions can be reached about the application:

Reflections

Depending on the use of this system, it may be useful to improve tax management or, on the contrary, it may hinder it.

Experience indicates that it will be useful when it is applied in a differentiated manner on a general automatic application up to a debt threshold and a limited time[3], and on an individual basis when the debt exceeds such threshold and the alleged transitory financial difficulties are verified, granted in differentiated terms according to the subject, the amount of the debt and the risk profile, with a reasonable financing rate and in certain cases with certain tax guarantees to safeguard the tax credit.

On the contrary, its granting has led to non-compliance in those countries that use it massively in an automatic manner, without distinguishing amounts, terms or risk profile, where no proof of financial difficulties is required, without fiscal guarantee and with a financial rate markedly lower than that of the banking system for commercial loans, that is, when the strategy applied constituted an escape for the defaulting debtor[4], instead of being an aid for the compliant taxpayer who wishes to pay his debt in the face of transitory financial difficulties.

Regimes that are lax with respect to their membership requirements also attract taxpayers who do not have economic difficulties, but who wish to obtain an economic advantage by[5] prejudicing tax revenue in a timely manner.

We should remember that, if a taxpayer has a “backpack” to pay his debt and in turn must comply with the current debt, a vicious circle can be incurred the larger his allowed debt is, since there will be a greater probability of his future default and the need to generate a new payment plan and so on[6].

Finally, it can be noted that an indicator to evaluate the management of the tax agency in this matter results from relating the percentage of the debt in installments with respect to the effective collection in a series of time periods.

[1]Manuel Rapoport “EL COBRO DE LA DEUDA TRIBUTARIA: POLÍTICAS Y PROBLEMAS ADMINISTRATIVOS” (1968) CIAT Assembly, Buenos Aires.

[2]Among other antecedents of breaches.

[3]“FORUM ON TAX ADMINISTRATION SUCCESFUL TAX DEBT MANAGEMENT: MEASURING MATURITY AND SUPPORTING CHANGE” OECD (2019). It highlights as an effective strategy to maximize collection prior to enforcement actions and therefore, in certain circumstances, to apply payment plans.

[4]“Collection and Recovery Manual” (2016), CIAT.

[5]With this “spread” they will make investments in speculative economic or financial activity to obtain a greater economic benefit. In turn, this situation generates unfair tax competition with their market competitors that have complied in a timely manner with the payment of their taxes.

[6]In many LAC countries, the possibility of including in a payment plan the debt from previous expired payment plans encourages tax abuse and generates serial defaulters.

11,966 total views, 6 views today