Mining Boom, fiscal policy and corruption (ii)

The Accuracy of Tax Instruments

The change introduced in the way of calculating mining royalties is not justified. The Former MR did not have a negative impact on the investment decisions of the companies of the sector as the theory implies. Between 2004 and 2011, investment in mining was multiplied approximately nine times and the profits of the 10 main mining companies were multiplied in a little more than five times.

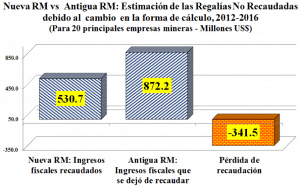

The New MR – supposedly more advantageous than the Former MR is being paid since November 2011. However, the investment experienced a reduction of 57.2% between 2013 and 2016. A similar trend is observed in mining earnings. Therefore, to say the least, for the period under analysis and in the specific case of Peru, the taxation of ad-valorem royalties did not affect investment nor the mining earnings. Instead, the New MR did affect the receipt of mining income by the Government. According to our own estimates, in 2012-2016, 20 main mining companies paid by way of the New MR, US$ 342 million less than what they would have had to pay under the scheme of the Former MR.

Prepared by the author.

Accordingly, a characteristic of the tax mining policy implemented in Peru during the decade of bonanza was its extreme passivity and complaisance, which did not allow an increase in tax revenues to the same extent as the extraordinary profits of the sector. It was rather a “regressive” tax system, in the sense that it did not allow the increasing participation of the Government in the mining income. Tax revenue collection from mining income was below the international standards. Although in 2005-2008, the Government obtained an annual average of 54.9% of the mining income before taxes, this result decreased to 33.5% in 2009-2012, and 18.8% in 2013-2016.

The need for alternate tax instruments

Since February 2016, the international price of some metals has recovered. Even though there is no possibility of approaching the peaks achieved during the recent mining bonanza, it is also true that this recovery occurs at a level established above the pre-bonanza levels. Therefore, the drop in the price of metals starting in 2012-2013 did not represent a financial catastrophe for the mining companies, but rather a reduction in its extraordinary profits, which leads us to the following question: why then has there been a collapse in tax revenues related to the mining activity?

In this context, counting on a tax policy with the adequate instruments for the optimum capture of mining income is a latent need for the nonrenewable natural resource exporting countries. That is, an alternate mining tax policy that may overcome the errors of the recent past, strengthen its institutions and which may go in hand with an environmentally sustainable mining investment policy.

A tax mining policy based only on already traditional instruments such as the Corporate Tax and royalties is not enough. Other tax instruments should be explored, such as those of the group of taxes that encumber “pure income”. They have the advantage of affording additional profits to the investors, but at the same time allow the Government to participate progressively in extraordinary earnings. This type of instruments should be applied as a complement to the aforementioned traditional instruments.

Likewise, mining royalties should be of the ad-valorem type, since those applied to earnings allow ample levels of freedom so that –in countries with weak institutions and high levels of evasion – the companies may manipulate their costs and expenses in order to reduce their profits. This is what the specialized literature classifies as “asymmetric information”, market shortcoming particularly stressed in mining: the mining producer is the only one with appropriate information on the structure and magnitude of the costs involved in its production process (Land, 2008), as well as on the technical and commercial aspects of its productive project (FMI, 2012). This allows a margin for the manipulation of costs that seeks to reduce artificially the rate of return on each one of the projects held by the same company.

In the case of Peru, from 2011, the costs and expenses of the mining sector increased at an annual average rate of 6.9%, even though sales decreased by 3.8%. This resulted in two complementary effects: 1) reduction of profits and –accordingly – of the Corporate Tax. 2) Greater refunds of Balance in favor of the Exporter (because purchases and tax credit were increased), thereby reducing the country’s net tax revenues.

Therefore, in order for this alternate tax policy to be successful, it is of utmost importance that the Tax Administration expand its control over the costs and expenses declared, the transfer pricing and avoidance practices. In the search for this objective, moving forward toward a greater involvement with the principles of the BEPS Action Plan is unpostponable. This is so because one of the main characteristics of the mining companies is that they are related with transnational economic groups, with a high capacity for aggressive tax planning, and what it implies in terms of the erosion of the tax bases and shifting of benefits.

References

BID (2013): Recaudar no basta: Los impuestos como instrumento de desarrollo; editado por Ana Corbacho, Vicente Fretes y Eduardo Lora. Washington D.C.: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.

BOADWAY, Robin y Michael KEEN (2013): Rent Taxes and Royalties in Designing Fiscal Regimes for Non-Renewable Resources.

FMI (2012): Fiscal Regimes for Extractive Industries: Design and Implementation; Prepared by the Fiscal Affairs Department. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

GÓMEZ SABAÍNI, Juan Carlos; JIMÉNEZ, Juan Pablo y Dalmiro MORÁN (2015): El impacto fiscal de la explotación de los recursos naturales no renovables en los países de América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile: NNUU – CEPAL.

LAND, Bryan C. (2008): Resource Rent Taxation – Theory and Experience. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

MENDOZA, Armando y José DE ECHAVE (2016): ¿Pagaron lo justo? Política fiscal peruana en tiempos del boom minero. Lima: OXFAM – CooperAcción.

TORRES CUZCANO, Víctor (2013): Grupos económicos y bonanza minera en el Perú. El caso de cinco grupos mineros nacionales. Lima: CooperAcción.

1,695 total views, 2 views today