Mining Boom, fiscal policy and corruption (i)

In this century, interest is renewed for the study of fiscal policy and its relationship with the income generated in extractive industries. Two main reasons explain this. On the one hand, in many countries, a significant portion of tax revenue comes from the income generated by the exploitation of non-renewable natural resources. On the other, the international price of raw materials-metals and hydrocarbons in particular- reached unprecedented levels during the 2003-2012 decade, which resulted in an unusual increase in tax revenues.

In Latin America, although the decade of mining bonanza boosted processes of socio-economic growth, the end of the expansive cycle of the commodities in 2012-2013 brought with it a slowdown of GDP and a decrease in collection, reminding the lesson that we have never finished learning: fiscal policy becomes fragile and unstable when it is based – mainly – on income originating from the export of raw materials.

However, as important as this finding is the question of whether during the mining boom, all that should have been collected was effectively collected. In other words, was the mining tax policy implemented during the Bonanza Decade (2003-2012) the most suitable for the optimal appropriation of the mining revenue?

The theoretical framework

The theoretical debate around the binomial fiscal policy-non-renewable natural resources, has revolved around what would be the ideal instrument of taxation; In other words, the one which: 1) leaves in the hands of the producer the normal return on investment, and 2) transfers to the state the highest level of tax revenue without affecting production.

The theory of taxation in the extractive industries classifies the instruments to obtain fiscal revenues between tax revenues and non-tax revenues. For some authors, the taxation in the extractive industries must be based on the income or benefits that a company obtains, i.e. in tax instruments (e.g. Corporate Income Tax); But not on their production or sales, i.e. in non-tax instruments (e.g. royalties). The advantages and disadvantages attributed to one or the other group of instruments generate heated discussions.

Royalties: are the payment that the mining company makes to the state for the use of a natural resource of public property. They can take various forms, but their general characteristic is that they are based on the amount of resources extracted, in terms of value or unit produced. Not a few authors consider that royalties are ineffective (Boadway and Keen, 2013) and/or they would greatly affect the investment decisions of mining companies (IDB, 2013; Gómez et al., 2015).

Income taxation: the taxes imposed on the mining income interfere less than the royalties in the production and investment decisions. This group of tax instruments includes a wide variety. The specialized literature identifies the so-called “tax on pure economic income” as the closest to the ideal of obtaining the maximum tax revenue without affecting the normal return on investment. The “pure economic income” of a non-renewable natural resource is defined as the surplus of the gross production value that is obtained after subtracting all the costs inherent to the exploitation of a deposit, including the remunerations of all the factors of production.

The case of Peru

Peru is a good case study to evaluate the problem raised in this article, namely, whether the mining tax policy was the most suitable for the optimal appropriation of the mining income during the rise in the prices of metals (2003-2012). In the years of greater effervescence of the mining boom, metal mining contributed to more than 60% of exports and contributed little more than 50% of the corporate tax.

Fiscal policy against extraordinary gains

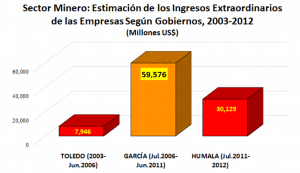

During the decade of mining bonanza, three governments succeeded in Peru: the one of Alejandro Toledo (July 2001-July 2006), followed by Alan Garcia (July 2006-July 2011) and the one of Ollanta Humala (July 2011-July 2016), each one with different predispositions regarding the mining tax policy.

During the government of Toledo (July 2001-July 2006), the mining tax policy was conformist. The payment of mining royalties was established in June 2004 (old MR), of the ad-valorem type; that is, a percentage of 1% to 3% was applied to the value of concentrate sales. A valuable tool, but that was of little help: the country’s largest mining companies did not pay royalties because they were covered by their tax stability contracts (CET in Spanish), although the Constitutional Court concluded that royalties are not a tax and therefore they should be paid by all companies in the sector.

During the Government of Garcia (July 2006-July 2011), the mining groups obtained their greatest profits. According to their own estimates, the mining sector’s extraordinary revenues due to the rise in the price of metals amounted to US $97,651 million during 2003-2012: 61% of that total was registered during that government.

Despite this, Garcia’s mining tax policy was the most passive and accommodating during the bonanza decade. The government kept collecting only royalties and corporate tax, without taking into account the wide range of alternative tax instruments applied in the world to attract income from the extractive industries (IMF, 2012). The largest mining companies continued without paying royalties: during June 2004 and September 2011, eleven companies would have ceased to pay US $1,619 million for royalties (Mendoza and of Echave, 2016), an amount higher by 44% than the royalties paid by the 90 companies that paid for them in the same period. Thus, the very partial implementation of the old MR demonstrated the capacity of the large mining companies to make their interests prevail.

At the same time, the García government rejected the application of a fiscal instrument such as the windfall tax, which taxes extraordinary gains. Instead, it chose to negotiate with the mining companies a “voluntary contribution” during the 2007-2011 period, a decision that was not fortunate in term of fiscal revenue: 1) 80,7% of the global payments of the so-called “voluntary contribution” were made by seven companies that were part of the CET program and therefore did not pay royalties. 2) The US $626 million that they deposited, represented only 51.9% of the US $1,205 billion that these same companies would have avoided paying as royalties (Mendoza and De Echave, 2016).

During Humala’s government (July 2011-July 2016), substantial changes were made to the mining tax regime (September 2011) with the aim of making royalties payable by the mining companies that did not pay them. The Special Mining Tax (SMT) was created, which began to be paid by companies without CET; The special levy on Mining (GEM), which charged companies that did not pay royalties; and the new mining royalty (new MR). Curiously, this change in the mining tax policy did not generate the strong rejection of the imposition of old MR in 2004. For what reason?: the three new tax instruments have a common denominator: the tax base is the operational profit, not the sales of concentrate as in the case of the former MR. Being applied on profits, the new MR and the GEM leave open the possibility that companies manipulate their costs and expenses in order to reduce their operational profit.

2,515 total views, 3 views today