Global Minimum Tax (GMT) (OECD Pillar 2): the decisive moment

The recent agreement reached by 137 countries and jurisdictions implies a profound reform of international tax rules in a globalized and digitalized world[1]. The agreement on Pillar 2 involved establishing multilaterally agreed limitations, to generate an additional tax collection of USD 150,000 million, from multinational companies that exceed 750 million euros in revenue, through a 15% effective tax rate.

The OECD will develop the model rules for their introduction into the internal legislation of each country in 2022, so that they will enter into force in 2023[2]. They made it clear, in turn, that this reform would not eliminate tax competition, but would provide greater stability to the international tax system and would generate greater legal certainty.

This pillar is based on the application of the GloBE rules, which require changes in the domestic legislation of each country, such as the ITI (Income Inclusion) that applies to the parent entity and the UTPR (Non-Taxable Payments) that is subsidiary to the ITI[3] which applies to the subsidiary, both at 15 %.

While the STTR rule (Subject to Taxation) with a maximum 9% aliquot on interest, royalties and other payments to be determined, requires changes in the DTAs, to block certain benefits approved in the DTAs [4].

The objective is to protect the tax base, avoiding its erosion or its transfer to countries with less or no tax burden on business income. If a state decides not to exercise its power of taxation at a reasonable minimum level in respect of a subsidiary, it must resign part of that power so that the jurisdiction of residence of the head office can tax that income until reaching the “minimum tax.”

The key question right now is: Does the GMT benefit emerging countries, or does it harm them?

As BARREIX argues (2021)[5] “… for the smaller economies, these agreements resemble an accession process to participate in the global markets of finance and trade,” regardless of the tax advantages or disadvantages they obtain.

According to the OECD, the GloBE rules will benefit emerging countries, namely:

From the new tax scheme, the following considerations arise:

The EU Tax Observatory (EUTAX Observatory)[9] conducted a research based on OECD data in the 2017 “country by country” report and made an estimate on the assumption that the GMT would be applied in the current year, to know the income it would generate and to which countries and regions it would benefit.

In its conclusions, we can highlight:

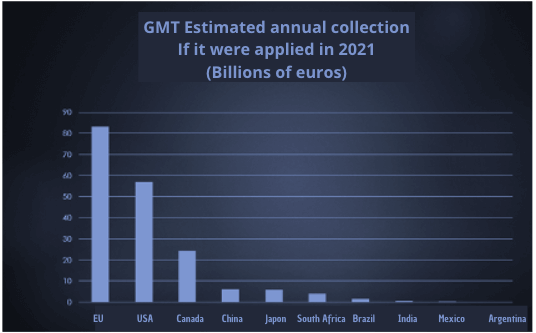

This graph shows the estimated income of the GMT, without the tax exclusions of the last agreement (” carve out”):

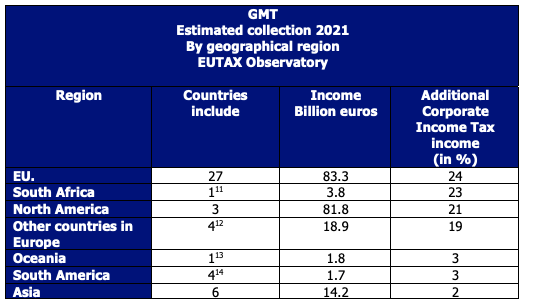

The following describes the additional income in the business tax that the respective regions will have, with respect to the tax that they currently receive from corporations:

Summary:

In view of this reform, emerging countries are logically cautious because of the novelty of the tax reform and the unknown effects of its application. At the same time, they expressed their disagreement with the low minimum tax rate set for the GMT.[15].

Finally, if the EUTAX estimates are confirmed, it would imply that the model involves a large asymmetry between the income of developed countries and the income of emerging countries, due to the application of the technical criterion of granting the power of complementary taxation to the country of residence of the parent company of the corporate group.

The author thanks Alberto Barreix for his valuable contribution and comment.

[1] ” Two-Pillar Solution to Address de Tax Challenges Arising from de Digitalization of The Economy”, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, October 2021, OECD (2021).

[2] Objectives: definition of GloBE rules and model treaty on the effects of tax rules (November/21), the multilateral instrument (MLI) for the implementation of the STTR in relevant bilateral treaties (mid-2022) and the general framework for the coordinated implementation of GloBE rules (end 2022).

[3] For example: the matrix is not located in a country applying Pillar 2. The deductions in the different entities of the group of payments that are not taxed with the minimum tax are limited to the entity receiving the payments.

[4] This rule allows source jurisdictions to tax certain intra-group payments at a higher rate than originally provided for in the convention, when such payments are taxed at a lower rate than the minimum in the jurisdiction of residence of the provider.

[5] Barreix, Alberto ” Por un nuevo mundial”, El Observador, 7/11/21, Uruguay.

[6] “The proposal of a Global Minimum Tax” (2021), Deloitte, Uruguay

[7] Average maximum aliquot in eighteen countries. Source CIAT.

[8] But arbitration strategies will be generated to obtain tax advantages in the face of asymmetries and gaps in the different regimes.

[9] ” Revenue Effects of The Global Minimum Tax: Country-by-Country Estimates ” EUTAX (2021) https://www.taxobservatory.eu/

[10] Earnings equivalent to 10% of the asset plus 8% of the payroll are exempt in the first fiscal year. Over ten years, exemption rates gradually decline to 5% of assets and payroll.

[11] South Africa

[12] The United Kingdom alone is estimated to have revenues of 11,000 million euros.

[13] Australia

[14] Argentina (100 m), Brazil (1,500 m), Chile (0) and Peru (100 m).

[15] They intended to fix them in a range of 21 to 25 %. Such a reduction would, according to EUTAX’s estimates, lead to more than double their estimated tax revenue.

7,422 total views, 3 views today