Access to financial information: a pillar of tax transparency and the fight against fraud**

In memory of Francisco Abea

Tax administrations, given the nature of their functions, require access to information held by the financial system. Ensuring tax compliance without knowing actual financial flows generates “short-sighted” tax administrations. This motivates them to implement unorthodox procedures to indirectly access information to deploy controls, taxes on financial transactions, for example.

It is also important to recognize that the protection of personal data (privacy) and commercial confidentiality are relevant rights. “Financial secrecy” contributes to such protection. Tax administrations must be able to access such information and the act of doing so should not be considered an infringement of such rights. This is because confidentiality is not “broken”, since “bank secrecy” is protected by “tax secrecy”, providing an equivalent level of confidentiality. Something similar happens when a tax administration exchanges information internationally, be it financial or other information subject to secrecy. The tax instruments for the exchange of information expressly establish the obligation to maintain confidentiality in accordance with the strictest standards.

The exchange of financial information between jurisdictions is now common practice. However, it is still very difficult for some countries to justify access to financial information. Why? The answer will depend on the history of each country and on political, social, and economic aspects. For example, high levels of insecurity and mistrust of public institutions, regulations to attract capital based on opacity, historical constitutional aspects, etc.

Failure to access this type of information and exchange it at the international level is more harmful to the country’s economy in both the short and long run than the potential negative domestic impacts of not accessing this information. Companies can also benefit from accessing such information because they can get to know their trading partners better, reducing their reputation risks. International investors and countries can also benefit because of improved transparency, rule of law and international credibility, which have a positive impact on productivity.

Financial information is key to improve taxation

The current crisis generated by COVID-19 is expected to be one of the greatest crises of the last 90 years. Economies plummet, as do tax resources. These are key to fiscal and economic stability, so financial information is indispensable to face this new scenario characterized by the crisis and the digital economy. At the international level, due to the need for tax revenues, one consequence will be even less tolerance for opacity.

In this sense, the lifting of bank secrecy is a fundamental pillar of the fight against tax fraud and money laundering, as well as an indispensable condition for cooperation between jurisdictions through the exchange of information, to combat these two scourges.

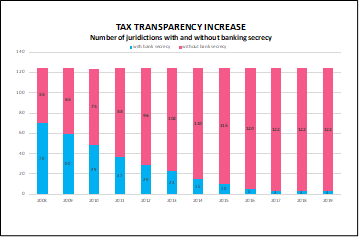

The good news is that there has been an international effort to implement principles of Tax Transparency (TT)[1] since the financial crisis in developed countries in 2008. The changes emerged in advanced economies because of fiscal needs arising from the crisis and because of the public pressure, in reaction to financial sector bailouts and the disclosure of aggressive financial planning practices by large savers and companies. In fact, some of the latter were favored by special treatments in the receiving jurisdictions themselves. In turn, it became clear that developing countries have also benefited from this TT process, given their higher levels of evasion and lower institutional capacity (collecting, regulatory and judicial bodies) and very limited control powers. Countries’ strong commitment to lifting bank secrecy is reflected in the attached graph. Additionally, the knowledge of financial data facilitated by international exchange included in the Global Forum’s Common Reporting Standard is also a valuable tool for better understanding the taxable subjects in their domestic operations. Finally, access to financial information on various risk activities is the crucial element of the set of (40) recommendations prescribed by FATF, including those on knowledge of the beneficial owner, for combating money laundering, and with it, drug trafficking and corruption, among others.

The good news is that there has been an international effort to implement principles of Tax Transparency (TT)[1] since the financial crisis in developed countries in 2008. The changes emerged in advanced economies because of fiscal needs arising from the crisis and because of the public pressure, in reaction to financial sector bailouts and the disclosure of aggressive financial planning practices by large savers and companies. In fact, some of the latter were favored by special treatments in the receiving jurisdictions themselves. In turn, it became clear that developing countries have also benefited from this TT process, given their higher levels of evasion and lower institutional capacity (collecting, regulatory and judicial bodies) and very limited control powers. Countries’ strong commitment to lifting bank secrecy is reflected in the attached graph. Additionally, the knowledge of financial data facilitated by international exchange included in the Global Forum’s Common Reporting Standard is also a valuable tool for better understanding the taxable subjects in their domestic operations. Finally, access to financial information on various risk activities is the crucial element of the set of (40) recommendations prescribed by FATF, including those on knowledge of the beneficial owner, for combating money laundering, and with it, drug trafficking and corruption, among others.

Access to financial data is crucial for risk analysis

According to the CIAT Database[2], 32 of 36 member and non-member countries in the Americas, Africa, Europe and Oceania empower their tax administrations to access domestic financial information. However, 30 of 36 surveyed countries have access to such data without the need to obtain judicial authorization. Both powers are fundamental to a series of control actions. First, there is no control of taxpayers’ finances in the century of digitalization and financial inclusion if regulation is not adapted to remove banking secrecy from internal operations of the jurisdiction. Secondly, access to financial data is a crucial element for risk analysis and information crossing since fund management (banking movements and electronic substitutes) is the mirror of actual movements for both direct taxation and consumption taxes. Finally, payments by any modality (cash, cards, electronic means, etc.) of the cash-based transactions, are the essential complement to the Electronic Invoice that records the movements of sales. In the future, the digitalized automatic checking of both records will be the basis of the main tools in the audit processes, for example: risk analysis, consistency of pre-prepared statements, or intra-group economic transactions, among others.

In another order, it is necessary to add that all efforts, especially those of multilateral actors, such as the Global Forum and the FATF, have as their main condition the security of data as a way of privileging the right to privacy of individuals and the business trade secret. Compliance with this condition is monitored through periodic evaluations of the processes of obtaining and exchanging information. At the same time, it should be noted that in order to guarantee respect for these two rights, it is essential that the jurisdictions implement civil and criminal sanctions in accordance with the seriousness of the acts for those who violate them, applying a higher rank to public officials.

Final thoughts and pending issues

Access to financial information for tax compliance control, both at the domestic and international level, is not an option; it is a necessity for tax administrations to ensure the proper application of the tax system. At the international level, it is a requirement to promote the reception of genuine investments and to be in line with global standards of transparency.

Currently, the vast majority of countries allow their tax administrations to access and even exchange domestic financial information through various mechanisms (on demand or automatically). The crisis will increase the need to implement controls to achieve tax revenues more efficiently, so integrating financial information into risk management systems is crucial. Similarly, one challenge to be addressed is access to financial information in the digital economy (e.g., crypto-currencies) and to the information of the Final Beneficiary, which, although not strictly financial information, is relevant information for transforming banking data into useful information in the framework of an investigation.

Transparency in general, and financial transparency in particular, – is a one-way street with no return. Those who fail to follow it will be confused in their institutional identity, short-sighted in the face of evasion and money laundering.

** We gratefully acknowledge the competent collaboration of Omaraly Blanco (CIAT) and the valuable comments of Fernando Velayos and Martín Ardanaz.

[1] The principles of the Global Forum on Information Exchange and Tax Transparency (GF), which is composed of 164 countries, are: (i) the elimination of bank secrecy and the elimination of bearer share companies; (ii) the exchange of financial information on request and automatically with other jurisdictions; and (iii) knowledge of the beneficial owner of the property.

[2] CIATData. Tax Transparency and Cooperation Database

6,137 total views, 7 views today